John Ericsson was born

in Vermland, Sweden, and immigrated to England in 1826 with a working

model of an engine design, which he called his Flame Engine. It appears

that this design was for an open cycle engine with internal combustion

which had functioned well at home in Sweden, but proved short-lasting

when fired with the hotter-burning English coal, and he abandoned the

project as a result. John Ericsson was born

in Vermland, Sweden, and immigrated to England in 1826 with a working

model of an engine design, which he called his Flame Engine. It appears

that this design was for an open cycle engine with internal combustion

which had functioned well at home in Sweden, but proved short-lasting

when fired with the hotter-burning English coal, and he abandoned the

project as a result.

In August of 1829, learning of a steam locomotive race that was to be held In October of that year, Ericsson formed a partnership with John Braithwaite, and in six weeks designed and built the steam locomotive Novelty. Without time to test their design, the locomotive was shipped-off to Rainhill for the trials. Weighing just over 2 tons, Novelty was much smaller than the other engines entered into the competition, and was the first to incorporate a cranked wheel mechanism. a design that would remain standard on steam engines until their demise 125 years later.

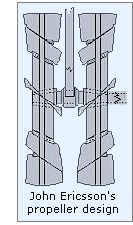

After the Rainhill Trials Ericsson turned to building ships and in 1836 he developed a successful screw mechanism for boat propulsion, which he called a "propeller." Ericsson continued to work on his Caloric engine designs, and created a more successful engine, which worked on a closed cycle with external heating. He demonstrated a working model of this "Caloric engine" in London in 1833. Ericsson's five horsepower model used two double acting cylinders, 14-inch hot cylinders, and a 10-inch diameter cold cylinder. A tubular heat exchanger was used to provide a form of regeneration. While Ericsson claimed priority of invention for this form of regeneration, Robert Stirling had in fact patented a similar system in 1816. Unfortunately, the demonstration did not meet with the rousing acceptance Ericsson had envisioned, and thus he confined his interests to standard steam power designs until 1838, when he constructed a 24 horsepower Caloric engine with a wire gauze regenerator. While the new design appeared to show promise, work on the design stopped when Ericsson, disappointed with the lack of support that he was receiving in England, immigrated to the United States the following year.

As a result of the success of the Princeton, in 1851 Ericsson managed to persuade his financial backers to build the Caloric Ship "Ericsson." The Ericsson was a two hundred and sixty-foot paddle ship powered by a four cylinder Caloric engine. Each cylinder was 168 inches in diameter, and boasted a six-foot stoke. Unfortunately, the ship was not a financial success, and even more unfortunately for Ericsson, it sank in storm off New York. As an almost personal insult to Ericsson, on being raised the ship was refitted with steam engines, which were in turn removed some time later when the vessel was converted to sail power. The ship continued in service as a sailing vessel until 1898 when it was driven ashore in a storm, off the West Coast of Canada. Ericsson was not deterred by the failure of the Caloric engine powered ship and continued to work on improving his Caloric engine concept, and was awarded patents for a number of improvements during the years 1855-1858.

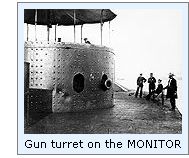

At the outbreak of the Civil War President Abraham Lincoln ordered the United States Navy to build a ship that could help defeat the Confederates. Several leading engineers, including Ericsson, were asked to contribute possible designs for this new ship. When the Navy rejected his design "the Monitor", Ericsson managed to obtain a special meeting with President Lincoln. Impressing Lincoln with his ideas and design, and Lincoln granted Ericsson the contract for construction of his warship. However, the Union navy had the last word in specifying that Ericsson had to complete the construction of his ship in one hundred days, or the contract would be voided.

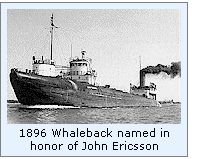

In 1896, the

American Steel Barge Company honored Ericsson by naming their new

whaleback steamer in his honor. The Ericsson continued to work the Great

Lakes until late 1963, when she was offered-up for use as a maritime

museum in Toronto, and then moved to Hamilton. Unfortunately, the city

of Hamilton was unable to raise the funds for her upkeep, and she

dismantled at the Strathearne Terminals in Hamilton in 1968. |

It was also the quickest and reached

speeds of 28 mph during the trials that took place on the first day.

This was 4 mph faster than the Rocket managed to attain during the

opening session. On the second day the Novelty's boiler pipe became

overheated and was damaged. To reach it for repairs, Ericsson and

Braithwaite were forced to partially dismantle the boiler. The

steam-tight joints had to be made with cement, which normally took a

week to harden. Braithwaite and Ericsson had to go out the next day, and

not surprisingly when the locomotive reached 15 mph the joints started

to blow. The damage was considerable and they forced to retire from the

competition.

It was also the quickest and reached

speeds of 28 mph during the trials that took place on the first day.

This was 4 mph faster than the Rocket managed to attain during the

opening session. On the second day the Novelty's boiler pipe became

overheated and was damaged. To reach it for repairs, Ericsson and

Braithwaite were forced to partially dismantle the boiler. The

steam-tight joints had to be made with cement, which normally took a

week to harden. Braithwaite and Ericsson had to go out the next day, and

not surprisingly when the locomotive reached 15 mph the joints started

to blow. The damage was considerable and they forced to retire from the

competition. Settling in New York, Ericsson quickly

delved back into his work and subsequently built eight experimental

Caloric engines between 1840 to 1850. These engines worked with an open

cycle with external heating, were equipped with wire gauze regenerators,

and used two pistons of unequal diameters. Ericsson continued to

experiment with ship design, and in 1849 he designed

"Princeton," the first metal-hulled, screw-propelled warship.

The "Princeton" was also the first vessel to have its engines

located below the waterline.

Settling in New York, Ericsson quickly

delved back into his work and subsequently built eight experimental

Caloric engines between 1840 to 1850. These engines worked with an open

cycle with external heating, were equipped with wire gauze regenerators,

and used two pistons of unequal diameters. Ericsson continued to

experiment with ship design, and in 1849 he designed

"Princeton," the first metal-hulled, screw-propelled warship.

The "Princeton" was also the first vessel to have its engines

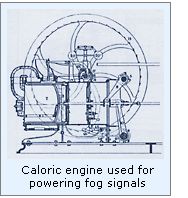

located below the waterline. Ericsson continued to improve his

Caloric Engine design, finalizing on an open cycle machine using both a

power piston and a supply piston, each fitted with valves. This engine

proved an immediate success and over 3000 were sold with in three years.

This machine was sold in various sizes, with cylinder diameters from 8

inches to 32-inches. A Caloric engine of this design generation was

installed at the Pilot Island Light Station to power the fog signal in

1854.

Ericsson continued to improve his

Caloric Engine design, finalizing on an open cycle machine using both a

power piston and a supply piston, each fitted with valves. This engine

proved an immediate success and over 3000 were sold with in three years.

This machine was sold in various sizes, with cylinder diameters from 8

inches to 32-inches. A Caloric engine of this design generation was

installed at the Pilot Island Light Station to power the fog signal in

1854. Work on the Monitor began in October

1861. In order to meet the construction deadline, work was undertaken at

nine different foundries, with the various components transported to

Greenpoint, Long Island where the final assembly was undertaken.

Launched in January 1862 at a total cost of $275,000, Ericsson managed

to squeak-by the 100-day deadline. The expertise of the northern

shipbuilders triumphed. When Ericsson began construction, the

Confederacy had already been working on the Virginia for six months. The

Virginia would not be completed until February 1862, a full month after

the Monitor's launch. Following the Monitor's launching, the ship

underwent several test runs and, after adjustments, set out for Hampton

Roads to meet the Virginia on March 6, 1862

Work on the Monitor began in October

1861. In order to meet the construction deadline, work was undertaken at

nine different foundries, with the various components transported to

Greenpoint, Long Island where the final assembly was undertaken.

Launched in January 1862 at a total cost of $275,000, Ericsson managed

to squeak-by the 100-day deadline. The expertise of the northern

shipbuilders triumphed. When Ericsson began construction, the

Confederacy had already been working on the Virginia for six months. The

Virginia would not be completed until February 1862, a full month after

the Monitor's launch. Following the Monitor's launching, the ship

underwent several test runs and, after adjustments, set out for Hampton

Roads to meet the Virginia on March 6, 1862 Ericsson's inventions revolutionized

navigation and the construction of warships including his ship The

Destroyer (1878), which was designed to launch submarine torpedoes. He

was exploring the possibility of using solar energy, gravitation and

tidal forces as sources of power when he passed away in 1889.

Ericsson's inventions revolutionized

navigation and the construction of warships including his ship The

Destroyer (1878), which was designed to launch submarine torpedoes. He

was exploring the possibility of using solar energy, gravitation and

tidal forces as sources of power when he passed away in 1889.