|

|

|

| Click thumbnails to view enlarged versions | ||

| Huron Island Light Station | Seeing The Light |

|

|

|

|

Historical Information

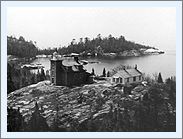

Thus, it was no great surprise to mariners when the venerable Captain Miller ran his side-wheeler Arctic and her cargo of passengers, freight and cattle aground on the easternmost island of the chain on May 29, 1860. While the Captain managed to get the passengers, cargo and even the cattle ashore to safety, the vessel was pounded by storm-driven waves, and crushed to kindling over the following days. Newspaper coverage of the loss of the Arctic served to bring the dangerous conditions around the islands to the publicís attention, and the intensity of pleas for a light on the Huron Islands increased in both frequency and fervor. The Lighthouse Board took up the call in its 1863 and 1865 annual reports to Congress, noting that the islands were "a constant source of anxiety to the navigators, wrecks having occurred frequently at this point." Congress responded favorably to the request with a $17,000 appropriation on July 26th, 1866, and the Detroit office immediately dispatched a survey crew to Lake Superior to select a site. The survey crew selected West Huron island, the westernmost of the chain as the best location for the new station. Basically nothing more than an outcropping of convoluted solid granite rock with deep fissures and chasms, the highest point on the island some 163 feet above lake level was chosen as the location for the lighthouse itself. While the site was selected and surveyed that year, it was not until September 2nd of 1887 that a clear title for the property was attained, and being so late in the season, work could not begin at the site until the following navigation season.

Plans for the station called for a duplicate of the station being constructed on Granite Island that same year. Built of granite blocks quarried from the islands themselves, the 1 Ĺ-story structure featured an integrated square tower 39 feet in height with a circular inner brick wall containing a set of 55 cast-iron spiral stairs which wound from the first floor to the lantern. With a landing on the second floor, these stairs also served as the only method of moving between the floors within the dwelling. Centered on the square gallery atop the tower, an octagonal cast-iron lantern was installed, and the fixed white Third and-a-half-Order Fresnel lens was assembled atop itsí cast-iron pedestal. By virtue of its location at the highest point on the island, the light boasted a focal plane of 197 feet. With the construction of a privy, oil house, boat dock and tramway, work on the station was completed that fall, with the light exhibited for the first time on the night of October 20, 1868. While the Board had been well aware of the fogs which shrouded the islands at the time of the original request, no funds for the construction of a fog-signal building had been included, since finds were available under a general appropriation for fog signals throughout the lighthouse system, and it was planned to tap this fund for the later construction of a fog signal on the island. However, the general appropriation was recalled by the Treasury on July 12, 1870, and without funding the fog signal could not be built. Requested funding was not forthcoming for almost a decade, when funds for construction were finally approved in 1880.

1887 saw the replacement of a stack in one of the signal buildings, improvement and extension of the tramway used to bring coal up the cliff to the signal building, and the installation of a steam-powered derrick for lifting supplies from the water below. This was also the fog signalís busiest season, as the keepers kept the whistles screaming their warning across Superior for a total of 361 hours. 1890 was also likely memorable for Huronís keepers as the stationís water supply was broken by ice in the spring, and the lighthouse was struck by lightning in June, tearing-out part of the cornice and damaging one of the buildingís side walls. While temporary repairs to this damage were made that year, it was not until the following year that a crew arrived at the island to make more permanent repairs.

The dawning of the new century saw continuing changes at the station, with the lightís upgrading from a wick lamp to incandescent oil vapor in 1912. At some time during the 1930ís a diesel-powered generator brought electricity to the station, allowing the electrification of both the dwelling and the light itself, and the subsequent conversion of the fog-signals to compressed-air powered diaphones. With the transfer of responsibility for aids to navigation to the Cast Guard in 1939, a crew of five Coasties took over responsibility for the station. Considering the old keepers dwelling to be too cold and uninhabitable, the Coast Guard built new "barracks-style" quarters near the fog-signal building in 1961, and installed a solar-powered 45,000 candlepower electric oscillating light in the stationís lantern. With the increased use of LORAN, Radar and GPS, the need for the fog-signal was deemed superfluous, and in 1972 the Coast Guard boarded-up the buildings and left the station for the last time, returning only infrequently to perform maintenance on the solar-powered light. Today, the Huron Islands are owned by

the US Department of the Interiorís Fish and Wildlife Service, and are

part of the Huron Islands Wilderness Area, which is administered by the

Seney National Wildlife Refuge. Consisting of a total of 147 acres, the

eight islands serve as a protected habitat for a wide variety of birds.

Interestingly enough, the easternmost island in the Huron Chain is known

to this day as Cattle Island, in memory of the cattle from the Arctic

that were marooned there long ago in 1860. The HILPA has a daunting task ahead of it, and needs all the support they can obtain. For additional information on the group, contact: The Huron Island Lighthouse

Preservation Association Or visit their

website |