|

Historical Information

The entrance into the St. Claire River from Lake Huron had long been

deemed of strategic importance. Named after General Charles Gratiot, the

engineer in charge of its construction, the Fort Gratiot military

outpost was established at the entrance to the river in 1814, and

ensured the security of vessels making the passage.With the surge in vessel traffic on Lake Huron in the early 1800's, the

need for a lighthouse to guide vessels into the river and away from the

shallows at the River entrance became a matter of increasing importance.

In response to this need, Congress appropriated $3,500 to construct a

lighthouse "near Fort Gratiot, in Michigan Territory" on March

3rd of 1823.

The contract for construction of the lighthouse and keepers dwelling was

awarded to Captain Winslow Lewis of Massachusetts. Lewis was the

inventor of the patented Lewis Lamp, which the Fifth Auditor had

universally adopted as the primary source of illumination in the

nation's growing inventory of lighthouses. A staunch supporter and ally

of the Fifth Auditor, Lewis had branched out into the business of

lighthouse construction, and as the frequent low bidder, was being

awarded a growing number of contracts to fulfill the nation's need for

navigational aids on the East Coast. The contract for construction of the lighthouse and keepers dwelling was

awarded to Captain Winslow Lewis of Massachusetts. Lewis was the

inventor of the patented Lewis Lamp, which the Fifth Auditor had

universally adopted as the primary source of illumination in the

nation's growing inventory of lighthouses. A staunch supporter and ally

of the Fifth Auditor, Lewis had branched out into the business of

lighthouse construction, and as the frequent low bidder, was being

awarded a growing number of contracts to fulfill the nation's need for

navigational aids on the East Coast. Lewis sub-contracted the construction of the tower and keepers dwelling

that would become known as the "Fort Gratiot Light" to Mr.

Daniel Warren of Rochester New York. Work commenced on the structure,

but appears to have been running far beyond the scope of the original

bid, since Congress appropriated an additional $5,000 for

the project's completion on April 2, 1825. With the completion of construction on August 8th of that year, Fort

Gratiot Light held the honor of becoming the first lighthouse in the

State of Michigan.

Rufus Match & Jean B. Denoyers served as temporary keepers until the

selection and appointment of a permanent keeper. The new tower stood 32

feet in height, with a diameter of 18 feet at the base, tapering to a

diameter of 9 ½ feet at its top. The lantern room was equipped with one

of the customary Lewis Lamp systems. George McDougall, a former Detroit

Lawyer of some ill repute was selected as the lights' first official

keeper, and arrived to take responsibility for the station in December

of that same year. Rufus Match & Jean B. Denoyers served as temporary keepers until the

selection and appointment of a permanent keeper. The new tower stood 32

feet in height, with a diameter of 18 feet at the base, tapering to a

diameter of 9 ½ feet at its top. The lantern room was equipped with one

of the customary Lewis Lamp systems. George McDougall, a former Detroit

Lawyer of some ill repute was selected as the lights' first official

keeper, and arrived to take responsibility for the station in December

of that same year.

Even with the major cost overrun, it became quickly apparent that the

structure was both poorly designed and constructed. McDougall's reports

indicated that the stairs were so steep that they had to be climbed

sideways, and the trapdoor into the lantern room was barely large enough

for a man to squeeze through. While McDougall no doubt reported with

truth on this situation, it must be noted that he was reputedly a short

man with a weight in excess of 300 pounds, and as such hired an

assistant to perform all of his tower work! Even with the major cost overrun, it became quickly apparent that the

structure was both poorly designed and constructed. McDougall's reports

indicated that the stairs were so steep that they had to be climbed

sideways, and the trapdoor into the lantern room was barely large enough

for a man to squeeze through. While McDougall no doubt reported with

truth on this situation, it must be noted that he was reputedly a short

man with a weight in excess of 300 pounds, and as such hired an

assistant to perform all of his tower work!

During the summer of 1828, McDougall further reported that the tower was

cracking, and had begun to settle in such a manner that it was leaning

noticeably toward the East. Finally, reports from mariners indicated

that the tower was both poorly located and illuminated, since they found

that its' feeble light was virtually invisible until their vessels were

almost at the mouth of the River. As a result of continuing erosion at the foot of the tower caused by the

swift current in the river, the footings of the tower became so severely

undermined that the tower finally toppled to the ground during one of

Huron's infamous November storms in 1828. Congress acted swiftly, and on

April 2nd of 1829, appropriated $8,000 for the construction of a new,

improved lighthouse.

This time, the bid for construction was awarded to Lucius Lyons who was

the Deputy Surveyor General of the Northwest Territory at the time, and

would later go on to become one of Michigan's first US Senators. Lyons

crew began work immediately, and completed the reconstruction in

December of that same year. The new brick tower was 74 feet in height,

and 25 feet in diameter, and the lantern was once again outfitted with one of

the universal Lewis Lamp systems, which was fueled by whale oil, brought

in on the Erie Canal. This time, the bid for construction was awarded to Lucius Lyons who was

the Deputy Surveyor General of the Northwest Territory at the time, and

would later go on to become one of Michigan's first US Senators. Lyons

crew began work immediately, and completed the reconstruction in

December of that same year. The new brick tower was 74 feet in height,

and 25 feet in diameter, and the lantern was once again outfitted with one of

the universal Lewis Lamp systems, which was fueled by whale oil, brought

in on the Erie Canal.

Soon

after its' establishment, the new US Lighthouse Board determined that

the Lewis Lamps universally accepted by the prior Pleasonton

administration were significantly inferior to the French Fresnel lenses

being adopted throughout the rest of the world. After conducting

successful trials of the new lenses in a few East Coast lights, the

Board decided to upgrade all lenses throughout the system. As a result,

the Lewis Lamps were removed from Fort Gratiot in 1857, and the tower

was refitted with a Fourth Order Fresnel

Lens, which had an

intensity of at least four times that of the old Lewis lamps. Soon

after its' establishment, the new US Lighthouse Board determined that

the Lewis Lamps universally accepted by the prior Pleasonton

administration were significantly inferior to the French Fresnel lenses

being adopted throughout the rest of the world. After conducting

successful trials of the new lenses in a few East Coast lights, the

Board decided to upgrade all lenses throughout the system. As a result,

the Lewis Lamps were removed from Fort Gratiot in 1857, and the tower

was refitted with a Fourth Order Fresnel

Lens, which had an

intensity of at least four times that of the old Lewis lamps.

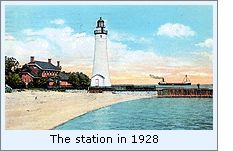

As

lake shipping continued to rise dramatically in the early second half

of the century, it was determined that the Fort Gratiot Light needed

further upgrading. To this end, in 1861 the Government increased the

height of the tower to 82 feet, and the Fourth Order Fresnel was

replaced with a larger Third Order Lens, showing a fixed white light.

The old Fourth Order lens was taken to Saginaw and installed in the

Saginaw River Lighthouse.

The growing amount of railroad traffic in Port Huron created

confusion for many mariners when the locomotive headlamps were seen to shine

as brightly as the Fresnel in the lighthouse. The problem was remedied

in 1867, when the "fixed white" lens at Fort Gratiot was swapped with the

"fixed

varied with a flash" lens from the Pointe Aux Barques light. The growing amount of railroad traffic in Port Huron created

confusion for many mariners when the locomotive headlamps were seen to shine

as brightly as the Fresnel in the lighthouse. The problem was remedied

in 1867, when the "fixed white" lens at Fort Gratiot was swapped with the

"fixed

varied with a flash" lens from the Pointe Aux Barques light.

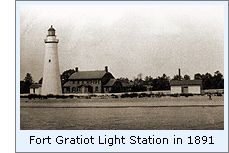

The original keepers dwelling was of wooden frame and clapboard

construction, and unfortunately burned to the ground in 1874. A brick

duplex was added to the site to provide quarters for the keeper and his

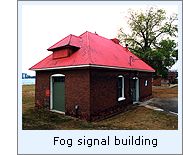

family along with the assistant keeper and his family. Fog signals have long been an integral part of the story at Fort Gratiot

Light. The first such unit was installed in 1871. A second steam-powered

diaphone fog signal unit was added in 1880, and both were replaced by a

steam-powered diaphone system housed in a brick building in 1901, which

still stands today.

The tower was again severely threatened during the great freshwater

hurricane of 1913, when it was almost washed from its foundation. After

weathering this storm within the tower, Captain Frank Kimball, the

keeper at the time, was quoted as saying "I watched waves as high

as 30 to 40 feet pounding on the lighthouse, and I think if the storm

had lasted another hour the lighthouse would have been wiped-out."

In order to help protect the foundation from such future poundings,

Kimball installed a three-foot high brick and mortar retaining wall

around the lake side of the tower the following year. This wall is still

standing today, and has become an integral feature of the tower

landscape. The tower was again severely threatened during the great freshwater

hurricane of 1913, when it was almost washed from its foundation. After

weathering this storm within the tower, Captain Frank Kimball, the

keeper at the time, was quoted as saying "I watched waves as high

as 30 to 40 feet pounding on the lighthouse, and I think if the storm

had lasted another hour the lighthouse would have been wiped-out."

In order to help protect the foundation from such future poundings,

Kimball installed a three-foot high brick and mortar retaining wall

around the lake side of the tower the following year. This wall is still

standing today, and has become an integral feature of the tower

landscape.

In 1933 the tower was outfitted with a green

DCB-24 Aerobeacon,

and was completely automated. With a range of 18 miles, the DCB-24

exhibited a one half second flash in every 15 seconds. The optic has

now been changed to a Vega rotating beacon which exhibits a similar

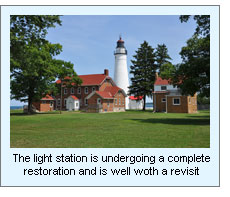

characteristic. The

five acre lighthouse grounds and all associated buildings were

transferred to St. Clair County through the National Historic

Lighthouse Preservation Act in 2010. The county entered into a

partnership with the Port Huron Museum, and the partners began

restoration in 2011.

Keepers of

this Light

Click here

to see a complete listing of all Fort Gratiot Light keepers compiled by

Phyllis L. Tag of Great Lakes Lighthouse Research

Seeing this Light

The

light station grounds are open to the for

public throughout the summer season with tours of the tower

and station buildings scheduled throughout the day. Information on

open hours and programs available on the Port Huron Museum website here

or by telephoning 810-982-0891.

|