|

Historical Information

On the recommendation of

Representative Chipman, the Commerce Committee was instructed to

investigate into the feasibility of erecting a Light at Whitefish Point on

January 13, 1846. After the Commerce Committee provided positive

feedback relative to the importance of establishing the Light, Congress

appropriated the sum of $5,000 for the stationís construction on March

3, 1847. Assistant Land Surveyor James Piper was immediately dispatched

to Whitefish Point to select a site for the new light, and arriving at

the point on April 3, 1847, laid-out 115.5 acres site consisting of cranberry bog and

sand dunes for the station. With the selected reservation officially

recorded in July, work began on laying out the plans and specifications

for the stationís structures.

That summer, the irascible Horace Greely sailed into Lake Superior on

his renowned "go west young man" tour of the western frontier.

On seeing first-hand the dangers to maritime commerce represented by

Whitefish Point, and on learning of the fact that the planned lighthouse

had yet to be constructed, Greely penned a scathing article in the New

York Tribune, in which he reported that "On the whole lake there is

not a lighthouse nor any harbor other than such holes in the rock-bound

coast as nature has perforated. Not a dollar has been spent on them.

Congress has ordered a lighthouse to be erected at Whitefish Point and

has provided the means; a Commissioner has located it; every month's

delay is virtual manslaughter; yet the executive pays men to air

uniforms at the Sault in absurd uselessness, and leaves the lighthouse

till another season." That summer, the irascible Horace Greely sailed into Lake Superior on

his renowned "go west young man" tour of the western frontier.

On seeing first-hand the dangers to maritime commerce represented by

Whitefish Point, and on learning of the fact that the planned lighthouse

had yet to be constructed, Greely penned a scathing article in the New

York Tribune, in which he reported that "On the whole lake there is

not a lighthouse nor any harbor other than such holes in the rock-bound

coast as nature has perforated. Not a dollar has been spent on them.

Congress has ordered a lighthouse to be erected at Whitefish Point and

has provided the means; a Commissioner has located it; every month's

delay is virtual manslaughter; yet the executive pays men to air

uniforms at the Sault in absurd uselessness, and leaves the lighthouse

till another season."

Whether Greeleyís article had any influence on the timing of

construction is unrecorded. However, it appears unlikely since the

contract for the stationís construction was not awarded to Sandusky

Ohio contractor Ebenezer Warner until August 21, 1847, and construction

did not begin until the summer of 1848 with the delivery of stone from

Tahquamenon Island by 40-ton Astor-owned schooner FUR TRADER, one of the

earliest large commercial vessels to ply Superiorís waters. Warnerís

crew toiled through the remainder of the navigation season, with the

work finished on November 1.

On completion, the new stone tower stood 65 feet tall, with an

outside diameter which tapered from 30 feet at the foundation to 14 feet

below the stone deck. Six windows illuminated the tower interior, and a

yellow pine spiral stairway wound its way up from an entry door on the

ground level to an iron ladder which led the final 8 feet to the scuttle

door in the stone deck. An octagonal iron lantern centered on the stone

deck housed an array of thirteen Lewis

lamps, each equipped with a

14-inch silvered reflector. A simple detached stone dwelling stood 1 Ĺ

stories in height, and contained two rooms on the lower level and a

sleeping area within the attic. At completion, costs of construction at

such a remote location were found to be much higher than expected, with

the total costs for the station coming in at $8,298, which was $3,298

over the original estimate and appropriation. On completion, the new stone tower stood 65 feet tall, with an

outside diameter which tapered from 30 feet at the foundation to 14 feet

below the stone deck. Six windows illuminated the tower interior, and a

yellow pine spiral stairway wound its way up from an entry door on the

ground level to an iron ladder which led the final 8 feet to the scuttle

door in the stone deck. An octagonal iron lantern centered on the stone

deck housed an array of thirteen Lewis

lamps, each equipped with a

14-inch silvered reflector. A simple detached stone dwelling stood 1 Ĺ

stories in height, and contained two rooms on the lower level and a

sleeping area within the attic. At completion, costs of construction at

such a remote location were found to be much higher than expected, with

the total costs for the station coming in at $8,298, which was $3,298

over the original estimate and appropriation.

While James A Starr was appointed as the first Keeper of the

Whitefish Point Light on October 10, 1848, with construction completed

so late in the year, the decision was made to postpone exhibiting the

new light until the opening of the 1849 navigation season. Evidently

Starr must have had second thoughts about serving as Keeper of the

Light, as he resigned his commission on May 2, 1849, to be replaced by

James B Van Rensalaer. During his 1850 inspection of the station in

1850, District Superintendent Henry B. Miller noted that Ransalearís

conduct was good, and recommended that a fence be erected around the

reservation in order to keep "the cattle and Indians away from the

buildings." Regardless of Millerís observations on the Keepersí

performance, Rensalaer resigned his position on May 8, 1851 and was

replaced by Amos Stiles. Evidently living conditions at the remote

station were less than ideal, as a succession of keepers would resign

the position, with seven keepers resigning their positions over the

following decade.

At the dawning of the mid century, the maritime community rose in

anger at the dismally poor administration of the nation's aids to

navigation by the Fifth Auditor of the Treasury. Congress reacted in

1852 by forming the Lighthouse Board, to which it simultaneously

transferred responsibility for the management of all lighthouses. Made

up of individuals with maritime and engineering experience, one of the

Board's first priorities was to undertake a system-wide upgrading of

illumination technology, switching over from the universally adopted

Lewis Lamp to the vastly superior French Fresnel lenses. To this end, a

work crew arrived at Whitefish Point in 1857 to supervise the

replacement of the station's Lewis lamp array fixed white Fourth Order

Fresnel lens, thereby increasing the station's visibility range to 13

miles in clear weather. At the dawning of the mid century, the maritime community rose in

anger at the dismally poor administration of the nation's aids to

navigation by the Fifth Auditor of the Treasury. Congress reacted in

1852 by forming the Lighthouse Board, to which it simultaneously

transferred responsibility for the management of all lighthouses. Made

up of individuals with maritime and engineering experience, one of the

Board's first priorities was to undertake a system-wide upgrading of

illumination technology, switching over from the universally adopted

Lewis Lamp to the vastly superior French Fresnel lenses. To this end, a

work crew arrived at Whitefish Point in 1857 to supervise the

replacement of the station's Lewis lamp array fixed white Fourth Order

Fresnel lens, thereby increasing the station's visibility range to 13

miles in clear weather.

With the opening of the new lock at the Sault in 1855, a major boom

had been experienced in St. Maryís River and Lake Superior maritime

traffic, and a cry arose in the maritime community to improve a number

of the Lights marking critical points along the course. To this end,

Senator Chandler submitted a Bill before Congress on February 10, 1859

requesting that the Commerce Committee be instructed to investigate that

feasibility of improving the lighthouses at Whitefish Point and Manitou

Island in Lake Superior, and at Detour at the Lake Huron entry into the

St. Maryís River. With the opening of the new lock at the Sault in 1855, a major boom

had been experienced in St. Maryís River and Lake Superior maritime

traffic, and a cry arose in the maritime community to improve a number

of the Lights marking critical points along the course. To this end,

Senator Chandler submitted a Bill before Congress on February 10, 1859

requesting that the Commerce Committee be instructed to investigate that

feasibility of improving the lighthouses at Whitefish Point and Manitou

Island in Lake Superior, and at Detour at the Lake Huron entry into the

St. Maryís River.

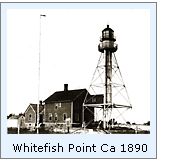

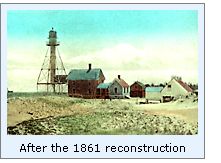

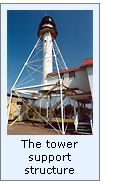

Contracts for the iron work and building materials for the new

station were awarded in 1861, and a work crew dispatched to the island

with the materials that summer. The tower was built of prefabricated

numbered cast iron sections which were assembled in a manner similar to

that of a giant erector set. The tower featured a six-foot diameter

cylindrical cast iron center cylinder of ľ inch plates, with its

interior wall lined with wood paneling to help reduce condensation.

Within this cylinder, a series of 57 cast iron stairs spiraled from the

entry at the lower end to the lantern, which was also fabricated of cast

iron sections. The center cylinder and lantern were supported by four

tubular iron legs which were bolted to concrete foundation pads. The

four legs were in turn supported by horizontal cross members with the

entire assembly provided rigidity by way of diagonal iron braces

equipped with turnbuckles. Interestingly, the central cylinder did not

reach the ground, but was suspended approximately 17 feet above ground

level, with entrance gained from the second floor of the two story wood

frame dwelling through an elevated covered passageway. As witness to the

importance placed upon the station, the tower was capped by a lantern

outfitted with a fixed white Third Order Fresnel

lens. Contracts for the iron work and building materials for the new

station were awarded in 1861, and a work crew dispatched to the island

with the materials that summer. The tower was built of prefabricated

numbered cast iron sections which were assembled in a manner similar to

that of a giant erector set. The tower featured a six-foot diameter

cylindrical cast iron center cylinder of ľ inch plates, with its

interior wall lined with wood paneling to help reduce condensation.

Within this cylinder, a series of 57 cast iron stairs spiraled from the

entry at the lower end to the lantern, which was also fabricated of cast

iron sections. The center cylinder and lantern were supported by four

tubular iron legs which were bolted to concrete foundation pads. The

four legs were in turn supported by horizontal cross members with the

entire assembly provided rigidity by way of diagonal iron braces

equipped with turnbuckles. Interestingly, the central cylinder did not

reach the ground, but was suspended approximately 17 feet above ground

level, with entrance gained from the second floor of the two story wood

frame dwelling through an elevated covered passageway. As witness to the

importance placed upon the station, the tower was capped by a lantern

outfitted with a fixed white Third Order Fresnel

lens.

Construction of

the new station continued through the arrival of winter in 1861, and

then resumed with the opening of the navigation. After the entire tower

structure was given a coat of dark brown paint, the new tower was placed

into service late in 1862. While the old tower was demolished

immediately, early photographs the new station show that the old

dwelling was left standing for a number of years. However, we have yet

been able to ascertain into what use it was placed, or when it was

finally demolished.

Construction of

the new station continued through the arrival of winter in 1861, and

then resumed with the opening of the navigation. After the entire tower

structure was given a coat of dark brown paint, the new tower was placed

into service late in 1862. While the old tower was demolished

immediately, early photographs the new station show that the old

dwelling was left standing for a number of years. However, we have yet

been able to ascertain into what use it was placed, or when it was

finally demolished.

During his annual inspections of the station in 1868 and 1869, the

Eleventh District Inspector reported that he found the tower and

illuminating apparatus condition to be "excellent," however,

he also observed that some plastering in the dwelling needed replacing

and that the station could benefit from the installation of a cistern in

the cellar into which runoff from the roof could be diverted as a supply

of drinking water. Also in 1869, it was first mentioned that maritime

commerce in the area would benefit greatly from the addition of a fog

signal at the station. While an appropriation for the establishment of a

number of fog signals throughout Lake Superior had been made, the

Congressional act of July 12, 1870 recalled all unexpended appropriation

balances back to the treasury, and thus no movement had been made on the

establishment of such a signal at Whitefish Point.

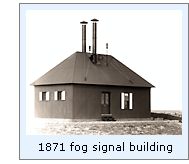

With a new renewed

appropriation in 1871, contracts were awarded for furnishing a

horizontal locomotive boiler and 10-inch steam whistles for the station.

The fog signal building was erected towards the lake from the lighthouse

that year, and took the shape of a twenty-two foot by forty-foot

wood-frame building sided with corrugated iron sheathing. The inner

walls were lined with iron sheathing to reflect the heat generated by

the boilers, and the walls packed with a mixture of sawdust and lime to

provide insulation and to act as a fire retardant.

With a new renewed

appropriation in 1871, contracts were awarded for furnishing a

horizontal locomotive boiler and 10-inch steam whistles for the station.

The fog signal building was erected towards the lake from the lighthouse

that year, and took the shape of a twenty-two foot by forty-foot

wood-frame building sided with corrugated iron sheathing. The inner

walls were lined with iron sheathing to reflect the heat generated by

the boilers, and the walls packed with a mixture of sawdust and lime to

provide insulation and to act as a fire retardant.

The decision was made to change the stationís characteristic from

fixed to flashing in 1892, and flash panels were ordered to effect the

change. Also this year, a contract for furnishing the metal work for a

circular iron oil storage building was awarded, and delivered at the

Detroit lighthouse depot. The following spring, the flash panels and

iron work were loaded on the lighthouse tender AMARANTH, and carried to

Whitefish Point, where a crew erected the oil house and the District

Lampist installed the flash panels and rotating mechanism in the

lantern. In accordance with a previously published Notice To Mariners,

the characteristic of the Whitefish Point lighthouse was changed from

fixed white to fixed white with a red flash every twenty seconds on the

night of June 15, 1893. On May 15 of the following year, the intensity

of the light was increased through the installation of a second order

kerosene lamp within the Third Order lens.

With the increased workload represented by the fog signal station,

plans were underway in 1894 to add a Second Assistant Keeper to the

stationís roster the following year. To accommodate the additional

keeper, a construction crew arrived at the station on the opening of the

1895 navigation season, By June, the crew had modified the original

single family dwelling into a mirrored duplex layout, with separate

entrances and stairways for the Keeper and First Assistant, who lived on

each side. A small frame dwelling for the Second Assistant was also

built to the east of the main building. With the departure of the work

crew at the end of July, the crew had also laid concrete walkways

connecting the station buildings, and repainted the tower white in order

to help it serve as an improved day mark. Later that year, the ball

bearings on which the lens rotated were replaced by a mercury flotation

system. Through this system, the lens floated in a bath of mercury,

virtually eliminating friction. This change allowed the lens to be

rotated at four times the previous speed, and allowed the characteristic

of the Light to be changed on the opening of the 1896 navigation season

to a red flash every 5 seconds. With the increased workload represented by the fog signal station,

plans were underway in 1894 to add a Second Assistant Keeper to the

stationís roster the following year. To accommodate the additional

keeper, a construction crew arrived at the station on the opening of the

1895 navigation season, By June, the crew had modified the original

single family dwelling into a mirrored duplex layout, with separate

entrances and stairways for the Keeper and First Assistant, who lived on

each side. A small frame dwelling for the Second Assistant was also

built to the east of the main building. With the departure of the work

crew at the end of July, the crew had also laid concrete walkways

connecting the station buildings, and repainted the tower white in order

to help it serve as an improved day mark. Later that year, the ball

bearings on which the lens rotated were replaced by a mercury flotation

system. Through this system, the lens floated in a bath of mercury,

virtually eliminating friction. This change allowed the lens to be

rotated at four times the previous speed, and allowed the characteristic

of the Light to be changed on the opening of the 1896 navigation season

to a red flash every 5 seconds.

After 25 years of service, the fog signal building and steam plants

were showing significant signs of wear, and a sub contractor crew

arrived to begin rebuilding fog signal building on July 7, 1896.

Replacement boilers and machinery were delivered by the lighthouse

tender AMARANTH in September, and by October, all pipe connections were

made, the equipment painted pressure tested, and the new signal was

placed into service. Over the following years, a number of additional

improvements were made at the fog signal, with a tramway erected from

the fog signal to the shore in 1900, and the iron smokestacks replaced

by 40-foot tall brick chimneys in 1905. Two years later, 1907 would be

the Whitefish Point fog signalís busiest year, with the keepers

shoveling 43 tons of coal into the hungry boilers to keep the fog

signals screaming for 694 hours.

1912 saw the establishment of an electrically operated submarine bell

2,187 yards from shore in 1912. Designed to take advantage of the high

sound transmission properties of water, the new bell was designed to be

heard through the hulls of approaching vessels to inform them of their

proximity to the station during thick weather. On September 5 of the

following year, the lamp was upgraded to an Aladdin incandescent oil

vapor system with a remarkable increase in intensity from 320,000 to

3,000,000 candlepower. Yet another in a seemingly endless changes in the

lightís characteristic was undertaken in 1918, with the removal of the

red flash panels and a change to occulting white every 2 seconds.

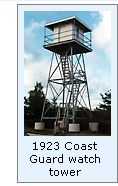

In 1923, the United States Coast Guard erected a life saving station

on the light station reservation. To serve this new crew, a number of

new buildings were erected, including an observation tower from which a

24-hour watch of the waters off the point could be conducted. The steam

power plant and 10-inch whistle were removed from the fog signal

building on August 15, 1925, and replaced with a more powerful

compressed air powered Type F diaphone sounding a group of 2 short

blasts and 1 long blast every minute. With the increased use of radio on

lake vessels, two months later on October 13, a radiobeacon transmitter

was installed in the fog signal building. Transmitting from a tall steel

tower, the transmitter emitted a single dash every 60 seconds during

thick weather, allowing mariners to easily fix their position by

triangulating from other such radiobeacon equipped stations on the lake. In 1923, the United States Coast Guard erected a life saving station

on the light station reservation. To serve this new crew, a number of

new buildings were erected, including an observation tower from which a

24-hour watch of the waters off the point could be conducted. The steam

power plant and 10-inch whistle were removed from the fog signal

building on August 15, 1925, and replaced with a more powerful

compressed air powered Type F diaphone sounding a group of 2 short

blasts and 1 long blast every minute. With the increased use of radio on

lake vessels, two months later on October 13, a radiobeacon transmitter

was installed in the fog signal building. Transmitting from a tall steel

tower, the transmitter emitted a single dash every 60 seconds during

thick weather, allowing mariners to easily fix their position by

triangulating from other such radiobeacon equipped stations on the lake.

In a vicious storm on October 11, 1935, the thirty year old

corrugated iron fog signal building was irreparably destroyed. The

following year a new cream city brick fog signal building was erected

immediately in front of the light tower. As one of the last shore-based

fog signal buildings erected, electricity had been installed at the

station and the building was designed specifically for diaphone and

radio operation, and featured a tall brick tower at the end facing the

lake from which the diaphone resonators protruded, allowing their sound

to carry above the dune and out into the lake.

With constant wave action threatening to erode the shoreline

immediately in front of the station, a number of protective piers were

erected along the shoreline in 1937. After assumption of responsibility

for the nationís aids to navigation in 1939, operation of the

Whitefish Point lighthouse came under the auspices of the Coast Guard.

However the lighthouse and life saving stations crews continued to

operate independently until April 9, 1947, when the two crews were

consolidated, and a six man crew was stationed full time to operate the

light. Fog signal, radio beacon and weather bureau station which had

also been established.

The Fresnel lens was finally removed from the lantern in 1968, and

replaced with a DCB224 aerobeacon, which with its simple and

reliable electronic motor and automatic bulb changer almost eliminated

the maintenance associated with the old Fresnel lens. With advances in

RADAR and LORAN, the old station no longer served its previous

importance, and the station was completely automated in 1971. The

station buildings were placed on the National Register of Historic

Places in 1973, and five years later, the Great Lakes Shipwreck

Historical Society was formed as a non-profit, educational institution,

dedicated to preserving the history and artifacts of the Great Lakes.

With Whitefish Point becoming the focal point for the organization, the

Great Lakes Shipwreck Museum was established in 1985. As part of their

involvement at the Point, the GLSHS has completely restored the keepers

dwelling and coast guard buildings, and most recently has been working

on building an accurate replica of the life saving boat house that used

to sit on the site. The Fresnel lens was finally removed from the lantern in 1968, and

replaced with a DCB224 aerobeacon, which with its simple and

reliable electronic motor and automatic bulb changer almost eliminated

the maintenance associated with the old Fresnel lens. With advances in

RADAR and LORAN, the old station no longer served its previous

importance, and the station was completely automated in 1971. The

station buildings were placed on the National Register of Historic

Places in 1973, and five years later, the Great Lakes Shipwreck

Historical Society was formed as a non-profit, educational institution,

dedicated to preserving the history and artifacts of the Great Lakes.

With Whitefish Point becoming the focal point for the organization, the

Great Lakes Shipwreck Museum was established in 1985. As part of their

involvement at the Point, the GLSHS has completely restored the keepers

dwelling and coast guard buildings, and most recently has been working

on building an accurate replica of the life saving boat house that used

to sit on the site.

Although 1983 saw the replacement of the diaphones in the fog signal

building with an electronic horn mounted on the tower, the Coast Guard

still maintains the lDCB224ís as an active aid to navigation with

maintenance performed by the crew from Coast Guard station Sault Ste

Marie.

Keepers of

this Light

Click here

to see a complete listing of all Whitefish Point Light keepers compiled

by Phyllis L. Tag of Great Lakes Lighthouse Research.

Seeing this Light

We arrived at Whitefish Point after eating lunch in Paradise.

This lighthouse complex is one of the most beautifully restore of all the lights we have visited, and with the addition of the Great Lakes Shipwreck Museum, has become one of the most visited. We toured the lighthouse keeperís residence, which as is the case in many lights, is set up in duplex fashion. All of the oak woodwork and trim has been replaced, and is now likely looks better today than it did when originally built.

After visiting the museum, we went into the theater, located in a secondary residence, and watched a video of the retrieval of the brass bell from the Edmund Fitzgerald, which sank 17 miles Northwest of Whitefish Point November 10, 1975. It was a very moving presentation, and some of the sequences gave a very dramatic view of just how tempestuous Superior can become.

Walking on the beach afterwards, it was very hard to conceive that such a peaceful place can become so incredibly violent.

Finding this Light

Take Wire Road North out of Paradise, and continue approximately eleven

miles to the lighthouse parking area at the end of the road.

Contact information

For information about visiting the Whitefish Point Light Station,

contact:

Whitefish Point - Great Lakes Shipwreck Museum

400 W Portage Ave

Sault Ste. Marie, MI 49783

(906) 635-1742

Reference

Sources

Congressional records,

various, 1846 - 1872

Annual report of the Fifth Auditor of the Treasury, 1850

Annual reports of the Lighthouse Board, 1853 - 1909

Annual reports of the Commissioner of Lighthouses, 1910 - 1939

History of Whitefish Point, Janice H Gerred, Inland Seas, 1984

Whitefish Point Lighthouse, unpublished chronology, Donald L

Nelson

Great Lakes Light Lists, various, 1861 - 1972

Draft Management Plan for Whitefish Point, Michigan Land Use Institute,

2002

Foghorns Saved Lives, Too, Vivian DeRusha Quantz, 1999

Lake Superior's Shipwreck Coast, Frederick Stonehouse. 1985

Photographs from author's personal collection.

Keeper listings for this light appear courtesy of Great

Lakes Lighthouse Research

|